B is the correct answer

Explanation:

This patient was envenomated by a rattlesnake, from the Viperidae family.

With summer approaching, snakes are emerging. For those of you hopping on your mountain bikes or lacing up your hiking shoes, be wary of these slithering creatures.

Epidemiology

About 8,000 snake envenomations occur annually in the US. Almost all of these are from snakes in the Viperidae family (Crotalidae/Crotalinae subfamily).

The good news is, with appropriate treatment, mortality is low. The estimated death rate in the US is about 15 people per year. This is much higher worldwide, with an estimated 130,000 deaths.

Up to 50% of bites are estimated to be dry bites, meaning no venom is injected. It is resource intensive for snakes to envenomate, so it is thought to be advantageous for them to inflict a defensive bite with no venom in certain situations.

Crotalinae snakes include the following:

- - Bushmaster

- - Copperheads

- - Cottonmouth

- - Eastern/Western diamondbacks

- - Massasauga

- - Puff adder

- - Sidewinder

Pathophysiology

Crotalinae venom in the US is primarily categorized as hemotoxic. However, a few species are predominantly neurotoxic, such as the Mojave rattlesnake (Crotalus scutulatus) in the southwest and the timber rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus) in the southeast.

Hemotoxic Crotalinae venom damages local tissue via hydrolases (e.g., phosphodiesterases, metalloproteinases) and hyaluronidase, which damages capillaries and leads to edema.

Diagnosis

Snakes belonging to the Viperidae family and Crotalinae subfamily have a characteristic pit-like depression behind their nostril that contains a heat-sensing organ to help find prey. This is why they are also known as pit vipers.

There is no absolutely reliable method to distinguish venomous from nonvenomous snakes. However, snakes from the Viperidae family tend to have triangular heads, elliptical eyes, and a rattle at the tip of their tails.

Labs to obtain include the following:

- - D dimer

- - Fibrinogen

- - Partial thromboplastin time

- - Prothrombin time

- - Platelets

It is important to check pulses, as significant edema can lead to compartment syndrome.

Treatment

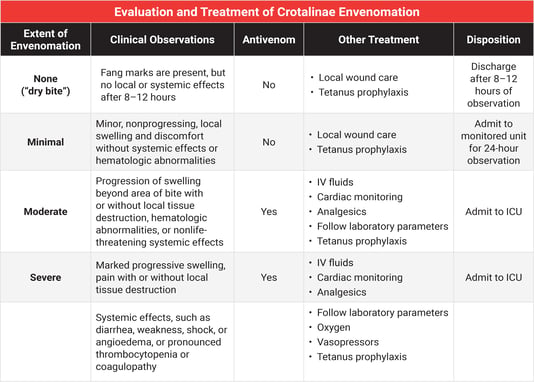

Observe all patients with suspected snake bites for 6 hours. An initially appearing innocuous bite can develop into more severe symptoms over that time frame.

All patients with coagulopathy and progression of swelling should be treated with antivenom. This patient did not have coagulopathy, but her pain and swelling continued to increase in severity. The local Poison Control Center was contacted, and antivenom was recommended due to pain radiating up to her inguinal region as well as the continued ascending swelling after several hours.

The Crotalidae polyvalent immune fragment-antigen binding antivenom was developed from sheep serum in 2000 and is the most widely available in the US. A second antivenom, Crotalidae equine immune fragment-antigen binding, was FDA approved in 2015. This newer antivenom has an additional binding site and confers a longer elimination half-life.

This patient received 5 vials of Crotalidae polyvalent immune fragment-antigen binding antivenom before her swelling abated. All patients who receive antivenom should be admitted to the ICU.

4-factor prothrombin complex concentrate is recommended for emergency reversal of life-threatening bleeding from intracranial hemorrhages or traumatic injuries. Although this may help with coagulopathy if antivenom is unavailable, antivenom is the preferred agent.

A Latrodectus (black widow) spider bite may present with similar pain and swelling. However, these spiders will not make a rattling sound.

If the patient has not received a recent tetanus vaccine, this would be recommended as part of routine wound care.

References:

- Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Brooks DE, Fraser MO, Banner W. 2016 annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 34th annual report. Clin Toxicol. 2017;55(10):1072–1252.

- Norris RL, Bush SP, Cardwell MD. Bites by venomous reptiles in Canada, the United States, and Mexico. In: Auerbach PS, Cushing TA, Harris NS, eds. Auerbach’s Wilderness Medicine. 7th ed. Elsevier; 2017:(Ch) 35.

- Rokyta DR, Wray KP, Margres MJ. The genesis of an exceptionally lethal venom in the timber rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus) revealed through comparative venom-gland transcriptomics. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:394.

- Warrell DA. Bites by venomous and nonvenomous reptiles worldwide. In: Auerbach PS, Cushing TA, Harris NS, eds. Auerbach’s Wilderness Medicine. 7th ed. Elsevier; 2017:(Ch) 36.

P.S. Want to test your knowledge with more questions like this? Take advantage of 15% off the Rosh Review Scholar EM Qbank. You'll get 25 new questions with detailed explanations + images and 50 CME annually!

Use code: RebelEMScholar